Because the internet is really big…

They say that a little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing, but I’m beginning to believe that a little bit of a hunch is far more risky. In the midst of a creative residency awarded by Adobe, my full-time responsibility is basically to explore hunches. On their best days, these inklings illuminate the path to learning something new. However, they can also be maddeningly indiscriminate—striking regardless of the beholder’s ability to test them. (And around major holidays, too! This is how my hunches work, at least—resulting in more than a few experimental, irrationally-pricey holiday cards.)

The “hmm… would that work?” which led to this particular project was initially directionless (and more problematic: appeared to demand that I learn Google Images’ ‘visually similar’ API to proceed, which wasn’t going to happen…) Thus, the idea ended up sitting dormant for at least a year.

It relates to this test of the size of the internet: Could I make a tiny film using only search result images?

The internet expands at a rate of 1.8 billion images per day, (says a 2014 report) which makes almost anything seem possible. That sheer visual abundance got me wondering. At what point will every possible composition for every possible action be pictured online? Could these disembodied images be collaged-together to reconstruct a piece of film or music video? Or—like drawn cel-animation—can this internet glut actually create the illusion of an action that never actually happened? And, most importantly for my selfish creative impulse: Are we there yet?

Both design and art are extremely permissive investigative tools. They arm the curious with a way to test out theories too far-fetched, uncommunicatable, or strange to otherwise pursue. So I just started making things to see what was possible.

The most basic animation is the classic bouncing ball. In spite of what the search result grid says, a bouncing ball does not hover in the air like a UFO. It came from somewhere and it going… well: down. Can the same internet that tore image-and-action apart make a ball bounce again?

What about airplane flight?

The inspiration for making discontinuous-bits-of-culture into something continuous goes back to 2011. Some of my friends camped out on a sidewalk to see Christian Marclay’s The Clock. Like a loser with a deadline, I missed out—only catching it years later at MoMA. In the day-long film, Marclay recreates each minute of the 24-hour day using clips from films featuring the current time—on a clock or watch. It runs in perfect synchronization with the audience’s day (so: while a museum crowd slumps sleepily in their chairs at 6am, starlets hit snooze on the clocks onscreen.)

Seeing the film was a revelation. I easily forget that time itself (as days, hours, and minutes) is a human invention to make the observable passage of time (daylight cycles and seasonal cycles) predictable. Marclay’s film reminds that like all built structures, time itself can be reconstructed using a different set of parts.

However, in spite of inheriting this wealth of cultural wisdom and insight, I still couldn’t wrap my head around the perfect structure on which to hang my internet-image-vastness technique.

Then, after a characteristically-enlightening conversation with Maria Popova, it hit me: I should recreate a piece of film that also concerns itself with vastness and scale. The Powers of Ten. That’s it! I would make an homage to the Eameses’s the Powers of Ten.

I did this:

The final presentation solution is a physical flip book. Here’s how the little chunky things turned out (Eames paper!! woo!):

You can play with a digital version here:

How it was made

Initially, I thought I would be able to lean on Google Images’ ‘visually similar’ search function to find the compositionally-similar images, frame-by-frame, from the Powers of Ten.

However, this assumes that the bots indexing content on the internet would be interested in composition.

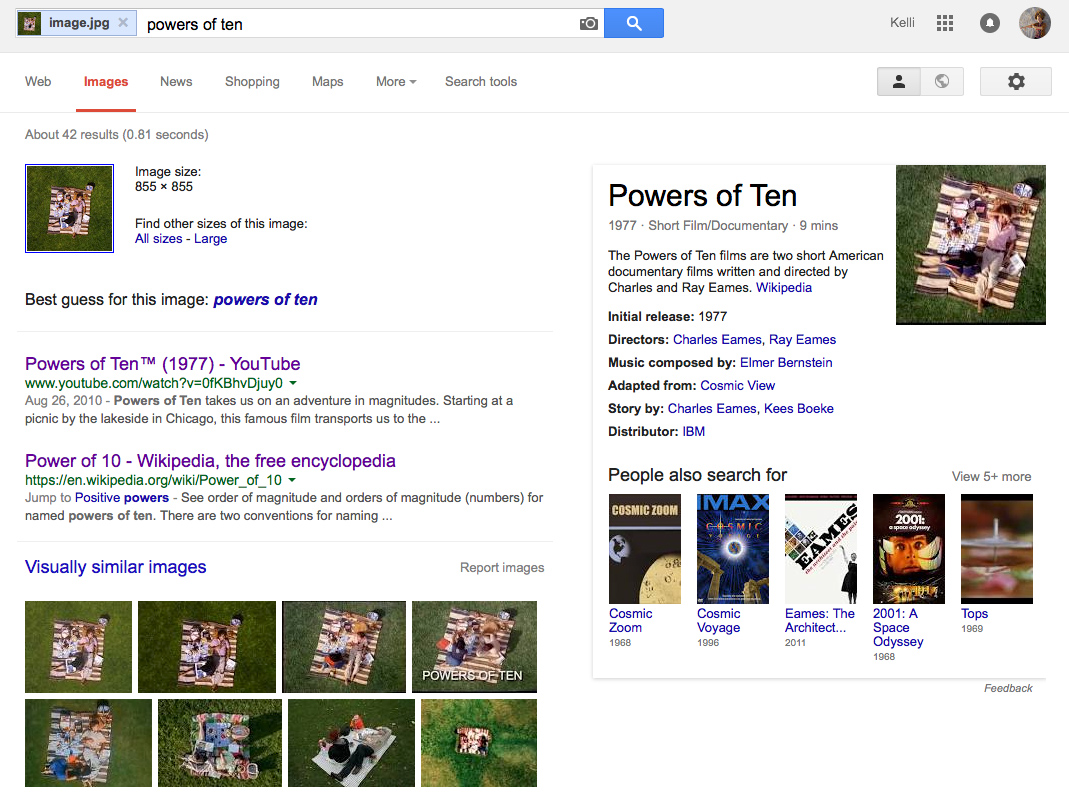

As it turns out, bots do not share my interests and could care less about composition. They’re interested in words. For example, this is what happens when I search for the sunbathing star of the film:

See what it did there? Sneaky. I did not type that text in the search field. It just KNOWS that this image is from the Powers of Ten. So it then cheats and uses that [text] knowledge to look for other images using the term “powers of ten” and related terms like “Eames.”

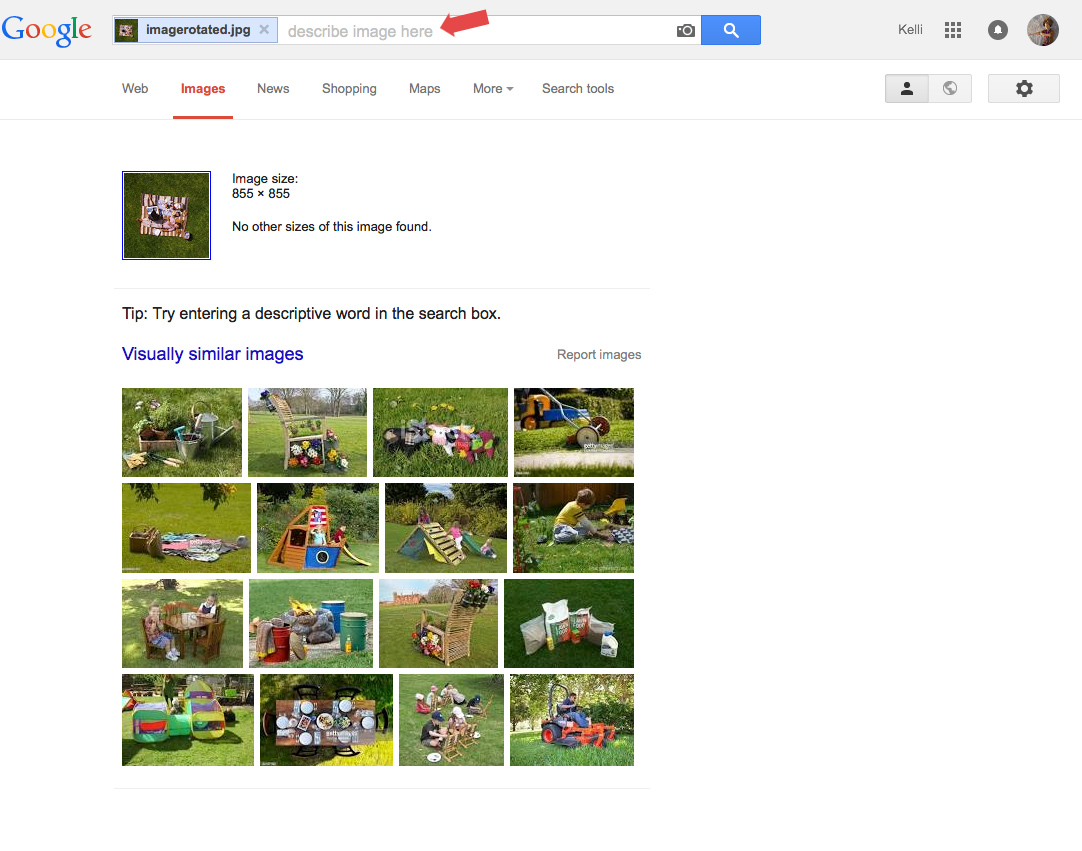

If you rotate the image, it stumps the dumb robot, but the images it finds are similar in coloration but NOT in composition. And it wants to be fed words:

So google image search was not a friend here. Instead, I embarked on a manual, supremely-human, very-subjective process of finding matching images. The beginning of the film, which pictures a hand on a chest, was replaced using images depicting the pledge of allegiance, dramatizing menstrual cramps, and demonstrations of rub-your-belly-pat-your-head.

The middle of the film shows a park adjacent to Meigs field in Chicago, which could only be recreated by the grace of The US Geological Survey’s wonderful Earth Explorer—a repository of photos taken from low-flying aircraft.

And the satellite imagery of the earth is from NASA, Apple Maps, and Google Earth.

**Fun fact: while the Powers of Ten situates those picnickers in Meigs field, the actual picnic-blanket was filmed with very tall ladders in Los Angeles, which was later masked-into a Miami golf course—and only then was finally placed into the triangular park space in Chicago.

An unexpected problem I encountered: there is simply not a natural circumstance on Earth that results in a single blanket on the Great Lawn. Or in the middle of a manicured park in Chicago. Or anywhere.

On a nice day in New York City, the sun rises, and blankets pulled from closets all over the boroughs spontaneously congregate—transforming all observable green space into a rainbow quilt. In creating the long zoom out of the park, the Eames had to fake the picnickers’ isolation. I, even with the whole internet at hand, had to do the same. I planted a ton of Miami golf course grass, deleting sunbathers, with the clone tool.

As big as the internet may be, it doesn’t yet have all possible pictures. Its bounty remains reigned-in by the laws of human nature and social sunbathing.

Update: A handful of people have expressed an interest in buying one of the flip books. I’m looking into whether that is feasible and will let people know via the newsletter. (You can unsubscribe right afterward.)

Related posts:

Comments

2 Responses to “Because the internet is really big…”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...[…] também versões interativa do vídeo acima, uma digital no site dela e outra física, no formato de flipbook (a imagem acima). E, abaixo, o vídeo clássico […]

[…] See it here. Read about it here. […]