Where Records come from…

“They were notorious for making their records out of dirt (literally) from the Milwaukee River.”

—Dean Blackwood (Revenant Records)

The path that music from the past takes to arrive in our hands today is often so tenuous—the odds so stacked against its documentation (much less its preservation)—that it is truly amazing that we have any sense of our musical heritage at all. The shellac recordings pressed at Paramount Records in the 1920s-30s have a particularly far-fetched and happenstance origin story: Paramount (no relationship to the film studio) was a furniture manufacturer which stumbled into the recording business as a strategy to increase the sale of their record players. The white owners began producing “race records” for an African-American audience (adopting an open-door recording policy in lieu of cultivating expertise in the field) and ended up accidentally capturing a crucial hot-minute of American culture. Artists of all stripes walked through Paramount’s doors, sung into their substandard microphones, and produced cheap, gritty records. What made this penny-pinching label unique was the composition of the crowds that passed through their doors: greats like Louis Armstrong, Ma Rainey, Blind Lemon Jefferson, as well as formidable talents whose names are lost to time. Now Jack White’s Third Man Records and Revenant Records, in conjunction with leading Paramount historian Alex van der Tuuk, have worked to grandly preserve this history and are releasing all of the tracks in two volumes—along with the gorgeous paper ephemera that music brings along with it. To mark the release of Vol. 2, I got swept up in the romance of it all and imagined what happened the day that Charley Patton walked into the studio. Here is the process of recording “High Water Everywhere, Part 1” at Paramount Records in 1930—re-enacted in paper stop-motion:

The thick, analog noise around Patton’s strumming is a reminder that some of history’s most inventive musicians were recorded on the most inferior equipment of their day. However, the fuzz is also a document of how those sound-grooves were gouged and pressed and smooshed into the disc. Each pop, hiss, and crackle maps to some physical imperfection in the record-pressing process.* This artifacting imbues the sound with an alluring dimension of tangibility (regardless of the sad reason for its presence).

*Dean Blackwood, of Revenant Records (whom I worked with closely), points out that Paramount’s sound contains even more artifacting than coeval shellac records due to their crappy materials: “The factory sat perched above the Milwaukee River riverbed. Dirt from that riverbed was one of the key ingredients in their shellac dough, which was lower on shellac content and higher on unexpected components like riverbed clay, cotton flock, and lamp black.”

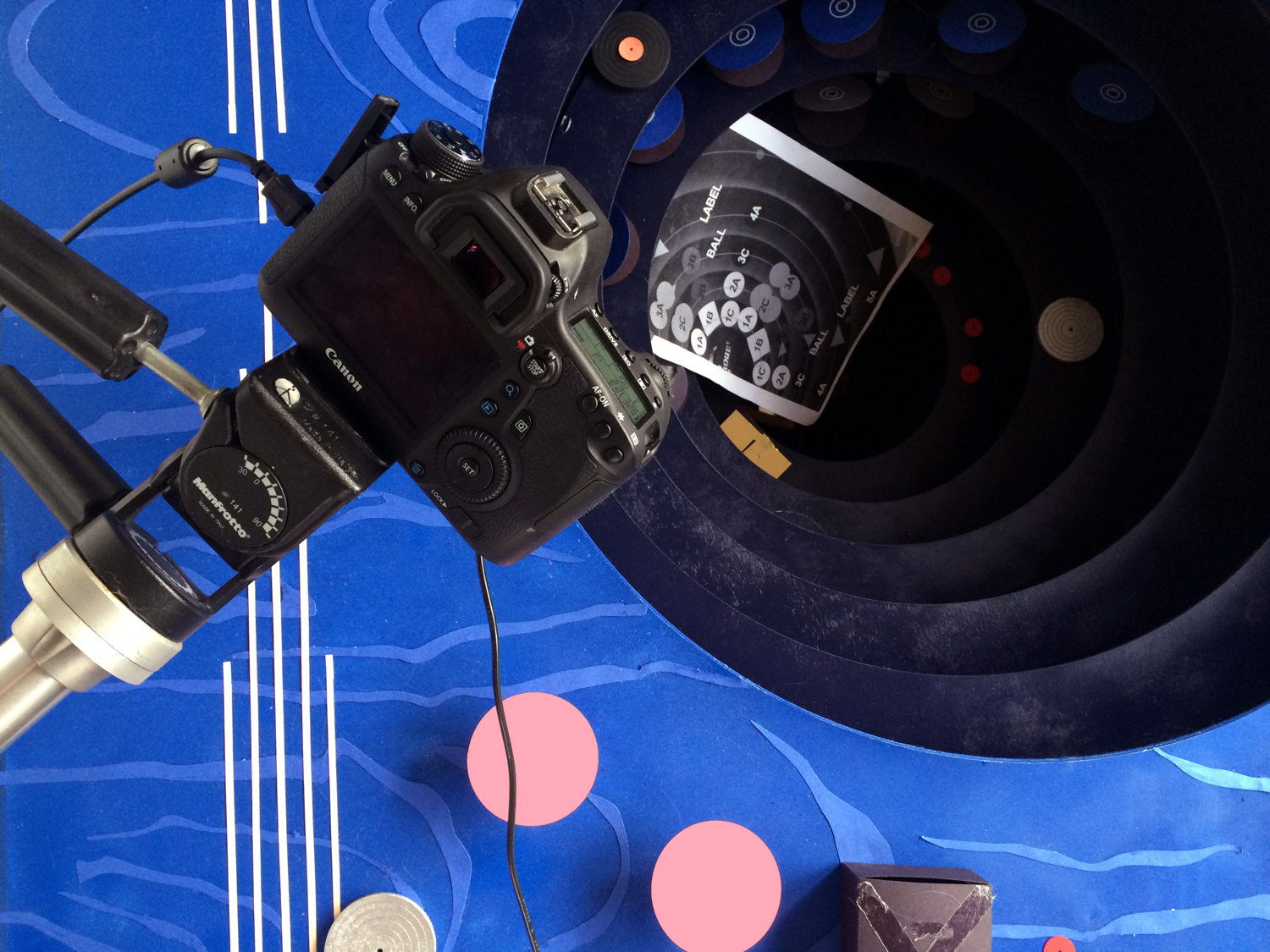

To make the video imagery match the fuzzy, flickering quality of that sound, I needed to cede some control over to the physical process itself. I generally end up balancing analog techniques (good for creating that inviting sense of realness/tangibiliy/surprise) and digital techniques (good for precision control over things like color, light, and timing) in my work—and realized that this project would lean towards the former. So I shot almost everything in-camera… and just smoothed over distracting imperfections in post. (Unwise? Sure. But really the only way I could envision doing it—given the subject matter.)

Before shooting anything, Dean and I schemed back-and-forth for weeks (doing sketches, storyboarding, typing book-length emails) to determine the “plot” and shot list—and to ensure that everything was historically accurate. Then Daniel Dunnam, Alina Melnikova and I jumped into building and shooting—the point at which many of the shots perfected in my daydreams fell flat when actually shot. So there was a LOT of on-the-set snap judgements and re-shooting, but we eventually got some good angles and happened upon the right lighting.

Counter to all common sense about stop-motion animation, I wanted to shoot the long, continuous factory scene in uncontrolled daylight to get an enhanced flicker (similar to the lighting in a humming industrial factory.) That lack of lighting control is apparent (especially towards the end of the sequence, where it is arguably a distraction), but was a better aesthetic match than studio lighting. (In retrospect, a better strategy would have probably been to light it halfway to the desired exposure with daylight-balanced studio lighting—to ensure that the shadows never dropped below a specific point, but allow the frantic peaks of brightness offered by the sunlight to take it the rest of the way there.)

As the disc moves along the conveyor belt, there are 7 main steps in the record-making process shown:

Note: This is a simplified and abstracted version of the process—we streamlined it a little bit for ease of comprehensibility, but didn’t distort the basic narrative of how a these records were made. These early animated sketches contain some continuity errors, which were eventually ironed-out in the final stop-motion version.

1. Molten wax is poured into a disc-shaped mold and allowed to harden into a disc.

2. Sound, transmitted by the microphone, vibrates a stylus which etches a groove of sound into the receptive wax disc. (One wax disc is made for each side of the record.)

3. The wax discs are then electroplated gold (this is a whole other level of magic process- read more here) to give it rigid strength, so it can be used as a mold.

4. The electroplated wax disc is used as a mold to cast a Nickel negative of Side A and Side B.

5. Those nickel pieces get loaded up into the disc stamper. (Both of them—despite what is shown here.)

6. Then, vóila!, shellac pucks begin dropping into the stamper and are flattened + embossed by the nickel negatives (resulting in a shellac positive).

7. Labels are applied. (The labels were actually hidden within the stamper from step 6 and applied simultaneously when the record was pressed. However, to minimize confusion for the viewer (and make this icing-on-the-cake step visible), I illustrated this as a separate step.)

(The End)

After devising these animated sketches (and receiving feedback on the accuracy of my dramatizations), I began building the physical set. Bryce McCloud from Isle of Printing cut the large plywood pieces for the record player and we painted, cut, and glued the set together over the course of several days.

The color palette and lighting were based on the proposed design of the box set from Dean (which was, in turn, based on the color palettes and noir lighting characteristic of the Machine-age Deco Era). There was a lot of chrome, rounded surfaces, high-contrast light, and a lot of indigo + pink used together.

Concentric circles and decorative parallel lines were also a prominent visual feature in industrial design objects of that era, which led to a record player set built of tiered, concentric circles. (And then… you can’t very well have a set of tiered, concentric-circles without at least one twirling Busby-Berkeley-esque sequence.) Creating the tiered set also allowed us to capture a realistic sense of space and parallax when entering the record/factory because we could actually drop the camera down into the center of the record:

After physically animating all of the sequences (and re-shooting and then re-shooting some more…) Alina and I worked on post-processing the thousands of individual photographs. It was a somewhat painful — if meditative — undertaking. So much for doing everything in camera! Meanwhile, Daniel worked on the sound design and editing everything together as the pieces of animation were completed.

“The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious…whoever does not know it can no longer wonder, no longer marvel[…]”

—Albert Einstein (via the poetic about page of Revenant Records)

Really, I’ll take any excuse to sit around and draw/make records all day… or recreate some of my favorite album art out of paper. But I’m particularly proud to have been able to contribute something to this incredible preservation project, which makes the music accessible to a new generation of listeners. And it was fun to indulge in creating a vision of a historical moment largely obscured by time.

To hear some of the tracks + more about the strange history of Paramount Records, listen to this interview with Dean on WNYC.

Also, check out this video of record grooves at 1000x magnification (you can see the sound waveforms!)

No related posts.

Hai kelianderson,nice work..

Top Blog Commenting Sites

Really beautiful piece of work – you really managed to capture the essence of those early recordings! How long did the project take?

Me ha maravillado este post, en realidad es que está muy cuidada la forma de expresarse, lo que hace disfrutar de la lectura. Una vez leí una cosa que hablaba de esto, y la verdad es que tambien me fascinó. Ojala que sigas redactando artículos parecidos a este, puesto que voy a visitar constantemente tu blog.