A month at the Exploratorium

C, M, Y (no K!) lightbulbs plus a magnifying glass equals this.

Striped light plus a rounded piece of plexiglass equals this.

Adrienne Rich’s poetry is best known for its impassioned critique of oppressive systems (typically: capitalism or the patriarchy.) Her poem, Hubble Photographs: After Sappho, showcases conflicted feelings regarding scientific enlightenment vs. technology’s destructive potential. It begins as a celebration of the sheer ecstasy experienced when gazing upon a photo of another galaxy. However, there is something almost… deliberately off in her suggestion that this impossibly-distant view is superior to that of her lover’s gaze.

Any tool of scientific magic—the poem implies—will eventually become a tool of destruction in humanity’s hands. It is, precisely, because it is far away, that the Hubble photography can be a source of joy…without the imagination reflexively fast forwarding to its eventual annihilation.

Robert Gilbert’s interpretation is the most interesting (and bleak) I’ve read:

“While our inventions may allow us to pierce the temporal and spatial armor that conceals these galaxies from our view, ultimately “we cannot hurt them”— and that fact is the true source of the joy they impart… We might call this an environmental sublime, necessitated by an age when no earthly landscape seems immune to human harm.”

I animated Amanda Palmer’s intense reading of this poem for this year’s “The Universe in Verse.” using a risograph printing method.:

Science’s duality of ‘tools humans use for the-ecstasy-of-understanding’ vs. ‘tools humans use for destruction’ is famously embodied in the contrasting legacies of the Oppenheimer brothers.

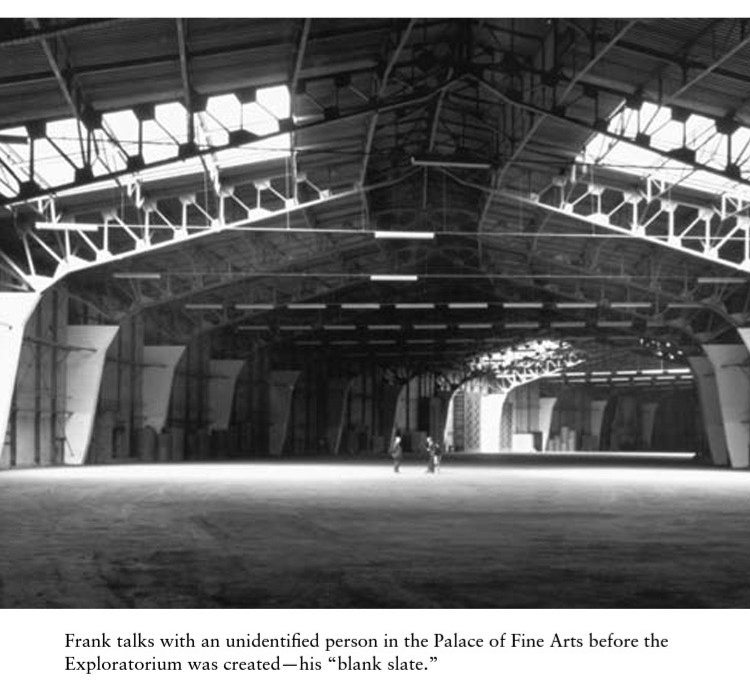

Frank Oppenheimer began his professional life working with his older brother, J. Robert, who would later become known as “the father of the atomic bomb.” However, McCarthyism put a premature end to Frank’s first career: After admitting an earlier affiliation with the Communist Party, being barred from all professional activity as a physicist, and being relegated to the fringes of society, he was left with little choice but to go his own way.

What he built out of this exile is nothing short of incredible. 12,000 (and a million) miles away from Los Alamos National Laboratory, Frank scrappily raised the funding to create a “museum of human awareness” within the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco. At the “Exploratorium“, visitors could tinker with the cosmic ray particles from distant galaxies in the Cloud Chamber, understand various methods to hack their own eyesight, and even manipulate the aesthetic balance in a Saul Steinberg drawing (to empathize/understand why the artist made specific compositional decisions.)

Within his un-museum, Oppenheimer accomplished what artist Robert Irwin refers to as “waking people from their non-thinking.” He sought to permanently change how people viewed the world they complacently lumbered-through through each day. To reveal that every mundane walk down the street is actually filled with an elaborate choreography of spacial, aesthetic, and material wonders and pleasures—wonders comfortingly agnostic to us and our wishes… impervious to our destructive impulses.

To impart such an awareness, lessons of physics were translated out of math and into matter, taking the form of interactive displays that visitors could touch, tinker-with, and attempt to break with their hands.

Oppenheimer’s biography, “Something Incredibly Wonderful Happens,” outlines the values that shaped the Exploratorium:

“sensitive observation, serious play, breaking the rules, a sometimes obnoxious insistence on transparency, respect for ordinary people, and a tolerance for chaos.”

Here’s what he had to say about computers (lol*):

“There’s nothing a computer can do that I want done.” Everything a computer did was a simulation, and therefore not sufficiently transparent—or even “honest.” You couldn’t see what was going on inside the box. Besides, computers were “passive and addictive.” Technology, including the technology of chips, is insidious,” he wrote. “It can carry us where we do not want to go if we follow mindlessly.”

*These ideas mirror those expressed in my own work so closely, I can’t believe that no one told me about this place until a few years ago.

I was initiated into the Exploratorium as an Osher Fellow on May 6th, so that I might “hang out and think and collaborate” for about a month—meeting almost everyone there.

I approached it with the perspective and pile-o-projects of an artists residency, and their beloved open Exhibits Workshop generously lent me a workbench… and so I transported my desk-mess from Brooklyn to San Francisco. I discussed new exhibit ideas with their creative director, Tom Rockwell (<- come for his infectious enthusiasm, stay for the Jane Aaron paper stop-motion at 18:00.), went on a Light Walk with Ken Finn, learned how Paul Dancstep is translating mathematics into touchable metaphors, brainstormed cool event invitations with the graphic design team, talked art with Claire Pillsbury and Kirsten Bach for hours and hours, watched experimental films with longtime film curator Liz Keim, contemplated “how do images work?” with fellow Fellow Scott McCloud, and built radios with the since-the-beginning exhibit guru, Dave Fleming.

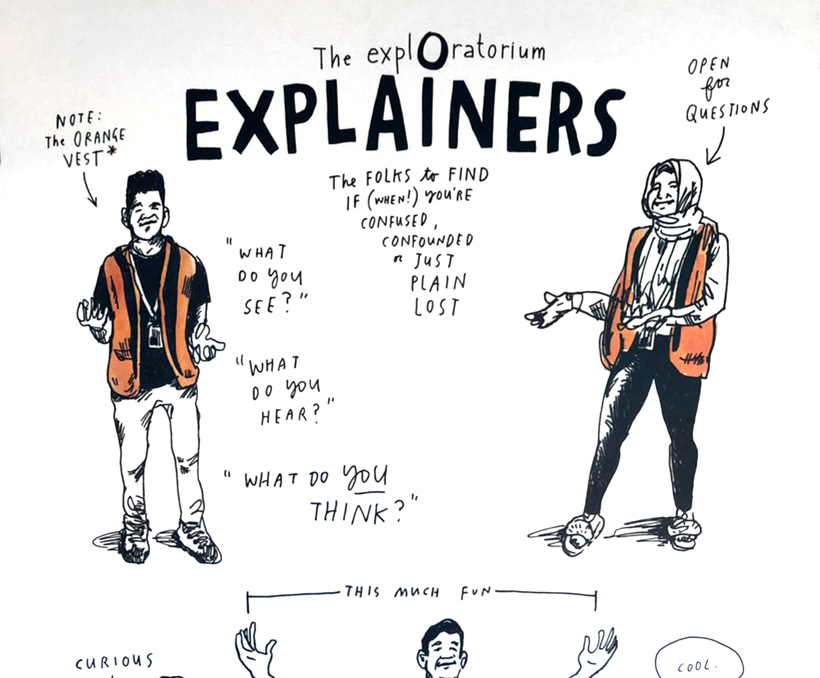

…And got to hang out with people whose literal/actual job title is “Explainer” (explainer is my favorite category of human!)

Illustration by Wendy MacNaughton

Here is a stream-of-consciousness tour of what I saw, did, and learned:

Binary number counter prototype on the workshop floor. (Made me think of SFPC—where they’re always seeking-out new physical metaphors to make the logic of binary numbers clear to new students.)

All the secrets…

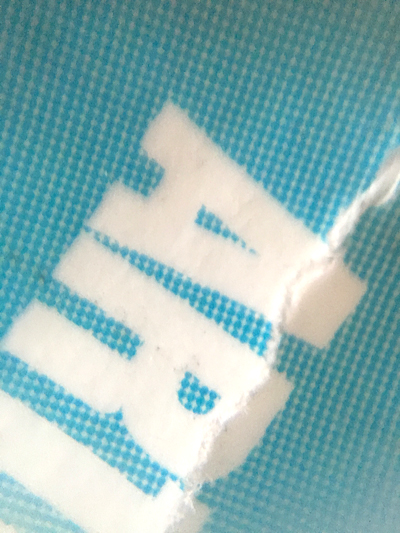

This is a collection of moiré magnification tests from The Tinkering Studio. These are acetate sheets printed with halftone screens of varying densities. When overlaid, the regularity of the grid confuses the brain’s pattern-seeking tendencies—creating the illusion of magnification where there is none. (This can be made with shapes other than dots too! More about that here.)

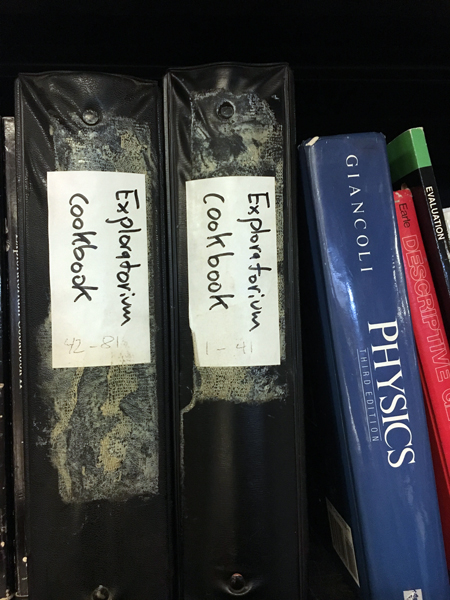

The Stanford Library digitized a pdf of this here. Note: You may have to “download” to view it.

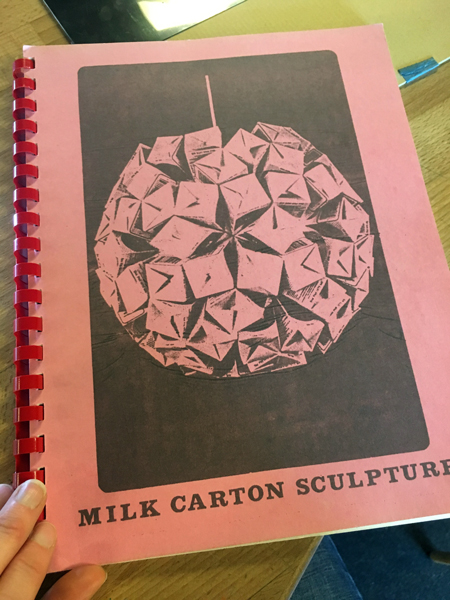

Karen Wilkinson and I also recreated one of Ruth Asawa’s milk carton sculptures (the influence of her teacher, Buckminster Fuller, is very apparent here.) To make these forms, she cut the cubic volume of a school lunch milk container into half-inch strips. Those strips may then be latticed together and stapled at the crossings to create a modular, reconfigurable structure:

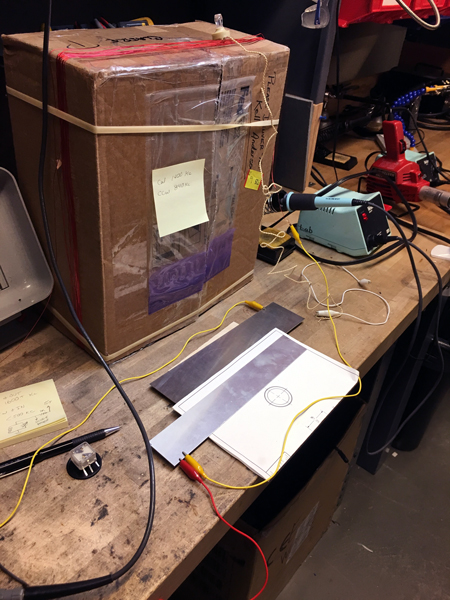

Dave Fleming, who has been inventing exhibits at the Exploratorium for over 40 years, took an interest in my desire to figure out how the format of a book might be used as an interface on radio waves. (Dave is responsible for the radio exhibits on the Exploratorium floor.) There are so. many. ways to build a radio. The coolest thing that Dave realized (which I’ll now fritter-away at developing) is that two sheets of conductive material moving against each other can work effectively as a tuner.

Also- that the wound coils of a radio antenna—if placed on a bellows or similar structure—might be spaced farther apart to change the frequency. Here’s the super-fun mess we made (we picked up some pretty awful AM talk radio 🙂 ):

I caught the tail-end of an installation using Rayform, a technique invented at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, which creates imagery by molding completely clear plastic. There is nothing visible until you shine a flashlight through it.

The Teacher’s Institute at the exploratorium develops maximally accessible (low-cost, easy-to-use) exhibits, experiments, and demonstrations for teachers to employ in their classrooms. For whatever reason, it has always seemed completely reasonable to me to comb through kid’s science experiment books for graphic design inspiration. So… really: we all just got along swimmingly!

They’ve discovered these 6-cent lenses from laser pointers can be used on a smartphone camera to capture microscopic worlds.

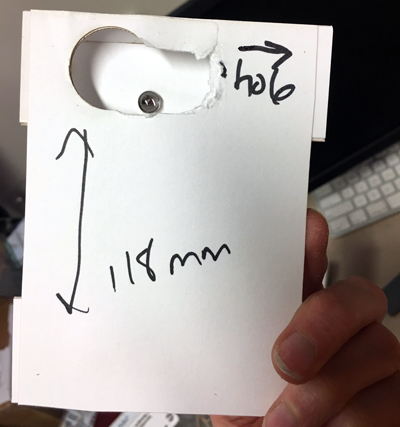

However, the tolerance for the focal distance required is incredibly unforgiving. If your hand wiggles a mere millimeter, the subject is thrown completely out of focus. To make the lenses more viable, I prototyped a paper “sled” to give the tool stability and ease focusing-woes. Here are some photos and videos of the prototyping process:

Sliding the holder/sled across a five dollar bill in truly-awful office lighting.

A newborn snail!

Eyeball on a five-dollar bill.

Denim is surprisingly complicated up close.

The spine of Artforum magazine.

The surface of a blondie.

Prototyping, making adjustments…

Just a completely-unnecessary amount of fretting went into deciding that design 2 was better than design 1 (it is definitely better… although, it could definitely still be much better.) Anyway, including this to show how it works.

I also iterated through 10 different versions of the next pop-up book I’m releasing (I was literally prototyping until the second my badge expired.) I don’t want to discuss it too much before I’m 100% sure that the manufacturing hurdles are worked-out, but… the paper mechanics work [sigh: finally…] is very pleasing:

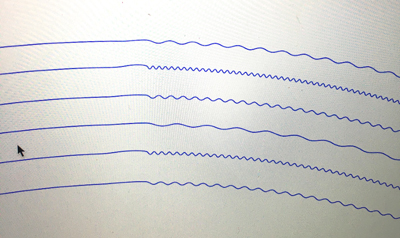

At an SFPC salon a couple of months ago, Dr. Jo Kazuhiro, placed a record made out of scratched paper in my hand and it kind of blew my mind. I thus began digging into Amanda Ghassaei’s fascinating experiments, where she seems to make records out of almost any material. (She has written a processing script to convert songs to wiggles.)

However, interestingly, paper doesn’t have the resolution to “hold” complex sound. Anything more complex than a beep is pure static. The layered sound one finds in recorded songs (I tried a Joy Division song) just sinks back into being noise again.

Basically: all recorded sound we hear is a palimpsest of another instance of sound. But one can draw sound that lacks an original acoustic origin. A sound is just a wave, a wave is just a wiggle. This seems to—in fact—be the only kind of sounds which paper will support. Here is what perfect beeping tones look like up close in Illustrator:

I then scratched them into the paper’s surface with a vinyl cutter (that 6-cent microscope came in handy here!):

This is what it sounds like:

…maybe this will turn into booklet of incessant beeping???

At the end of the fellowship, the social media team (Gayle and Sewon!) and I played around in the photo studio for their #50facesofexplo project… and they wrote this nice profile of my work:

“Human perception–and the illusion of magic when we see the edges of our own hardware’s limitations–is endlessly fascinating to me as artistic inspiration.” ⠀⠀

⠀⠀

Graphic designer and paper engineer Kelli Anderson creates surreal experiences with paper that both defy people’s expectations for humble materials, while demonstrating and explaining scientific phenomena. ⠀⠀

⠀⠀

Her paper explorations began with a simple paper record player she made for a friends’ wedding invitation in 2011. As the project became viral, she was struck by the attraction to lo-fi paper tech in this age of advanced tech, and she’s been prodding this question through her work. Her published work includes a functional paper camera pop-up book and a pop-up planetarium, “This Book is a Planetarium.” Her works highlights the superpower of paper mechanisms–that they do scale. A few of the satellites currently in space right now were modeled in paper using methods traditionally found in origami–fluidly jumping from book-sized and room-sized to galaxy-sized. ⠀⠀

⠀⠀

Over the past couple weeks, Kelli has been working as a “thinker-in-residence” Osher Fellow at the Exploratorium. She’s been exploring new connections and new project ideas stemming from conversations with Exploratorium staff, including a prototyping paper microscope stands, a pop-up record player book, and turning a book into a radio. ⠀⠀

⠀⠀

“You don’t need expensive tools, equipment, or even coding knowledge to make things that feel magical.”⠀⠀

⠀⠀

📷 by Gayle Laird, Exploratorium.

OK so… 10/10- Would definitely fellow again! Thank you so much to everyone at the Exploratorium.

No related posts.